Patrick Peter

“The arms race must be stopped”

The transition to 2025 marked the end of a long chapter for Patrick Peter, who will no longer be heading up Peter Auto‘s events this year. However, the sprightly septuagenarian will certainly not be short of activities in the coming months. Before setting sail on new adventures, he shares an insightful analysis of the evolution of historic racing over the past 40 years.

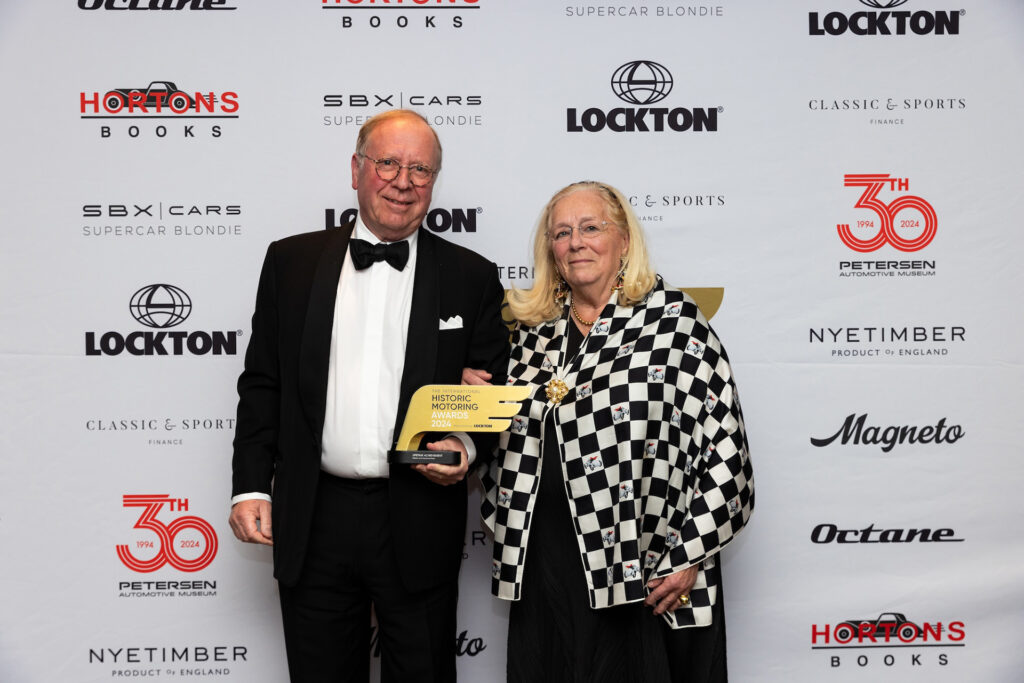

A key figure in modern motorsport—having spearheaded the revival of GT racing in the 1990s (BPR, Barth-Peter-Ratel) then of endurance racing in the 2000s with ACO (ELMS)—Patrick Peter is also one of the driving forces behind the growth of historic motorsport since the 1980s. We owe him the Tour Auto, Le Mans Classic and a host of series contested on European circuits. We met him at the International Historic Motoring Awards in London, where he and his wife Sylviane received a prestigious award in recognition of their remarkable careers.

What was a historic race like forty years ago?

Patrick Peter: At the Coupes de l’Âge d’Or at Montlhéry, a significant number of cars arrived by road, participated in the races, and then left by road. The others came on simple trailers, usually hitched to a Range. Today, I often say that some competitors buy the motorhome before the car. The quality of the grids varied greatly. I remember a one-make series with Panhard single-seaters that were held upright by wire and made a barely audible sound. But we also had some truly beautiful cars. When we saw a Ferrari 250 Short Wheelbase, we knew it was the real one, as continuations didn’t exist. In the 1990s, at the Tour Auto, there were sometimes five or six Ferrari 250 GTOs. Today, at 50 million euros each, that’s unimaginable.

By the way, the first Le Mans Classic, in 2002, was only open to cars that had actually competed in the 24 Hours of Le Mans…

Yes, but at the time, the visionary Max Mosley [sic] allowed continuations to compete, against the wishes of the historic commission. With the rise in prices, there are now more of them every year. Some brave owners resist, like Conrad Ulrich with his Ferrari 250 GT SWB or Jean-Jacques Bally with his Maserati A6 GCS. Peter Auto is one of the last organisers to present high-value cars in competition.

What’s the secret to convincing these owners?

We need to reassure them. To do so, we must implement measures to moderate the more reckless drivers. For example, we amended our regulations about ten years ago, so that a competitor responsible for a collision is required to pay half of the repair costs for the vehicle he damaged. On occasion, we also penalised continuations.

On occasion?

Yes, because not everything can be written in the regulations. For example, there is no reason to penalise the owner of a beautiful Ferrari 512 replica entered in a CER race (Classic Endurance Racing). But if there’s a “real” Ferrari 512 and a “copy,” the second one should be penalised, otherwise it will inevitably be faster. The driver of a 3-million-euro car will always brake earlier than the driver of a 300,000-euro car.

Not to mention that the “modern” version is more efficient…

Yes, because its chassis is more rigid, and its engine is assembled with tighter machining tolerances. That said, all historic cars are faster now than they were in their time, by 5 to 10 percent. The settings are optimised by computers rather than by ear, and the welds and glues are of better quality. We can’t stop progress, even in historic racing. The challenge is to ensure that this increase doesn’t reach 20 or 30 percent.

“Preparers risk cutting the branch they’re sitting on.”

What can be done to limit this progression?

The imagination of a competitor to improve his machine, in a more or less legal way, is the same in historic as in modern. We must have constant technical checks to prevent any deviations. In 2024, about ten cars were disqualified after races organised by Peter Auto. We have found modern components in clutches and gearboxes. The checks in place are still not enough. The arms race must be stopped. My successor Marc Ouayoun and the Peter Auto teams are working on it.

Isn’t this an inevitable consequence of the professionalisation of the sport?

The positive side is that the rise of preparers has improved the cars’ reliability. In the 1990s, we used to overbook the entry list for the Tour Auto by 15 to 20 percent, in order to anticipate the loss of around forty cars in the last week before the start. The downside is that budgets have soared. I think preparers risk cutting the branch they’re sitting on, because even a wealthy owner may eventually wonder if it’s reasonable to spend so much money on a hobby.

Haven’t you contributed to this price increase?

Yes, in spite of myself. In the early 1980s, even Ferrari cars were sold for prices that would seem laughable today. One day, we noticed that Jaguar prices increased after a celebration of the brand at the Coupes de l’Age d’Or at Montlhéry. This trend was subsequently confirmed. Every time we launched a new Peter Auto grid, the price of eligible cars automatically started rising.

A round-the-world sailing trip passes through the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. Le Mans Classic passes through the Mulsanne Straight and Arnage.

What’s your greatest achievement?

The BPR, the Tour Auto, Chantilly… It’s hard to choose. The first Le Mans Classic was very difficult to organise. For me, it was out of the question to do it on the Bugatti Circuit. A round-the-world sailing trip passes through the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. Le Mans Classic passes through the Mulsanne Straight and Arnage. That is how it is. The problem is the closure of the long circuit, which is expensive. The inaugural edition was very unprofitable, to the point that I had to sell some of my personal collection cars. I’ve never regretted it, because we went from 20,000 to 200,000 spectators in less than 20 years.

And your biggest regret?

I don’t look back too much. I’ve always had difficulty bringing pre-war cars to our events, even though I love them. Unfortunately, that remains a very British thing.

What dreams do you still have to fulfill?

I want to go back to sailing. That’s why I settled in Brittany. I learned to sail when I was young. I even crossed the Atlantic. I wasn’t destined to have a career in automobiles. The communications agency that Sylviane and I ran had sports, jewellery and watch brands as clients. We would have stayed in those fields if Jean-Marie Reisser, at the time president of the ASAVÉ (Association of Vintage Vehicles), hadn’t approached us in 1982 to find sponsors for the Coupes de l’Âge d’Or.

You’re going to give up on cars?

No. When I was a child, I loved taking apart Solex scooters and mopeds. So I’m going to try to get back into mechanics. I’ve opened my garage, les Ateliers de Kerdrein. We have an 800 square metres space, very well equipped for mechanics, bodywork, and upholstery. It’s a workshop with a view, facing the sea, which is why we’ve installed a humidity control system. We already have some very fine cars here, including a Jaguar XJ12 Broadspeed, a Ferrari 308 GTB Gr IV Michelotto and a Porsche 907.

Will you get back behind the wheel in competition?

My Lotus XI and AC Bristol are just waiting for me! To begin, I plan to participate in the 2025 Peking to Paris challenge with my three sons—Geoffroy, Josselin, and Marin—who will take turns accompanying me.

- Vladimir Grudzinski (CarJager)

- Patrick Peter (Peter Auto)

- Jérémy Rollet (Drive Vintage)

- Yvan Mahé (Équipe Europe)

- Julien Hergault (Classic Media)